Section 2.2 Can anything be expressed by quasi isometry?

Two metric spaces are the same if they are isometric. In the previous section we saw although there is no canonical word metric on a group, if we consider metric spaces only up to quasi isometry, then we do obtain something canonical: namely the quasi isometry class of word metrics coming from finite generating sets. The issue then becomes that maybe quasi isometry is too vague and that all groups are quasi isometric. For quasi isometry to be useful, it must be able to tell groups apart.

All finite groups are quasi isometric to the metric space consisting of a single point, so this viewpoint is not useful for the study of finite groups. We also see that quasi isometry is able to distinguish finite groups from infinite groups, but that isn't particularly impressive.

In this lecture we will show that the groups \(\ZZ\) and \(\ZZ^2\) are not quasi isometric and we will prove Theorem 2.2.5, the Svarc-Milnor Lemma, which has far reaching consequences such as the fact that if \(K \leq H\) is a finite index subgroup then \(H\) and \(K\) are quasi isometric. This gives us a limitation of how much can be determined by quasi isometry.

Let \(x\) be a point in a metric space \((X,d)\text{,}\) let \(r\gt 0\) be some number, then we define the closed ball of radius \(r\) about \(x\) to be the set

When it is clear from the context in which metric space a given ball lies, we will not bother explicitly giving the metric.

It is worth recalling from Exercise 1.5.1.4 that for any ball about the identity in the standard Cayley graph of \(\ZZ^2\text{,}\) we can find a generating set of \(\ZZ\) which gives the exact same ball about the identity. In other words, at small and medium scales word metrics will not distinguish \(\ZZ\) and \(\ZZ^2\)

The proof of the following is known as an asymptotic argument.

Proposition 2.2.1.

The groups \(\ZZ\) and \(\ZZ^2\) are not quasi isometric.

Proof.

We take the standard cayley graphs \(\cay{\{1\}}{\ZZ}\text{,}\) the line, and \(\cay{\left\{\BEmatrix{1\\0},\BEmatrix{0\\1}\right\}}{\ZZ^2}\text{,}\) the infinite grid, and equip \(\ZZ\) and \(\ZZ^2\) with the induced word metric.

Suppose towards a contradiction that \(\ZZ\) and \(\ZZ^2\) were quasi-isometric. Then there would exist a \((K,C)\)-quasi isometric embeding \(f:\ZZ^2 \to \ZZ\text{.}\) Consider the balls \(B(1,r) \subset \ZZ^2\text{,}\) on the one hand they look like diamonds and contain \(|B(1,r)|=O(r^2)\) points. On the other hand, because we have a quasi-isometric embedding we have a containment.

Since \(\ZZ\) is a line we have

Because the cardinality of \(B(1,r) \subset \ZZ^2\) grows faster than the cardinality of \(B(f(1)),Kr+C) \subset \ZZ\) the restrictions \(f|_{B(1,r)}\) will be far from injetive, in partiular as \(r \to \infty\) then maximal number of preimages of a point in \(B(f(1),Kr+C)\) via the restrictions \(f|_{B(1,r)}\) must also go to infinity.

Pick \(M\) so large that any subset of \(\ZZ^2\) with \(M\) or more elements must have diameter at least \(K\cdot(1+C)\) and pick \(r\) so large that some element \(z_0 \in B(f(1),Kr+C)\) has at least \(M\) \(f|_{B(1,r)}\)-pre images.

On the one hand there must be elements \(y,y' \in \ZZ^2\) such that \(f(y)=f(y')=z_0\) but \(d(y,y')\geq K\cdot(1+C)\text{.}\) But by definition of a quasi-isometric embedding we must have

but

which is a contradiction. It follows that there can be no quasi-isometric embedding from \(\ZZ^2\) to \(\ZZ\text{.}\)

So at least now we have established that quasi isometry is maybe not a completely useless notion as it can tell at least two groups apart. Quasi isometry, however, does have limitations and we will now explore these.

From now on we will asssume our spaces \(X\) are path connected metric spaces, the readier at this point is free to assume that \(X\) is a connected graph, all of whose edges have a given length (usually they have unit length). A path is a continuous mapping

and we can define its speed at \(s\) as

If \(X\) is a graph, viewing edges as isometric copies of intervals of \(\RR\) we can make sense of this for almost all values of \(s \in [0,L]\text{.}\)

Integrating speed gives arc length and we say that \(p\) is arc length parameterized if \(|\dot p(s)| =1\) for all \(s \in [0,L]\text{.}\) We say that a path is a geodesic if it is a shortest path between its endpoints \(p(0)\) and \(p(L)\) and we can define the path metric to be given by the minimal length of all paths joining two points. A metric space is called a geodesic metric space if its metric coincides with the path metric.

We assume the reader knows what a left group action

on a space is. We will use the \(\cdot\) symbol to denote the action of a group element on a point. We say that \(G\) acts by isometries on \((X,d)\) if for every \(g \in G\) and every \(x,y \in X\) we have:

For our current purposes it will be sufficient to only consider our metric spaces to be path connected graphs, but the results we state will be be more general. For our purposes a compact set is a finite subgraph. An action by isometries is an action by graph automorphisms. The action of \(G\) on a graph \(X\) is proper if the stablizer of any vertex is finite. The quotient \(G \backslash X\) of an action has vertices that conist of equivalence classes

and edges

and is itself a graph. The action of \(G\) on \(X\) is cocompact if \(G\backslash X\) is finite and a coarse fundamental domain is compact subset \(K \subset X\) whose \(G\) translates cover \(X\text{,}\) i.e.

With all this terminology out of the way, we can start proving results.

We will first state a useful result without proof. It follows from a careful consideration of the definitions.

Lemma 2.2.2.

If a group \(G\) acts properly, cocompactly and by isometries on a graph \(X\text{,}\) then \(X\) is locally finite, i.e. all vertices are adjacent to only finitely many edges. In particular balls of finite radius only contain finitely many elements.Lemma 2.2.3.

Let \(G\) act properly and cocompactly on a path connected graph \(X\) with a distinguished vertex \(p_0\) by isometries. Then the following are true:

- There is some \(r_0>0\) such that \(X = G\cdot B(p_0,r_0)\text{,}\) i.e. \(G\)-translates of \(B(p_0,r_0)\) cover \(X\text{.}\)

- The subset\begin{equation*} R_s=\{g \in G \mid g\cdot B(p_0,s)\cap B(p_0,s)\neq \emptyset\} \subset G \end{equation*}is finite for all radii \(s>0\text{.}\)

- Let \(r_0\) be as in Item 1. Then set\begin{equation*} S = R_{r_0}=\{g \in G \mid g\cdot B(p_0,r_0)\cap B(p_0,r_0)\neq\emptyset\} \end{equation*}is a generating set for \(G\text{,}\) i.e. \(G = \gen S.\)

Proof.

Let's first prove Item 1. Because the action is cocompact the quotient \(G\backslash X\) is a finite graph. Let \([v_1],\ldots,[v_k]\) and \([e_1],\ldots,[e_l]\) be the vertices and edges of \(G\backslash X\) respectively. For vertex each \([v_i]\) of the quotient pick some vertex \([v_i]\ni \hat v_i \in V(X)\) and for each edge \([e_j]\) of the quotient pick some edge \([v_j]\ni \hat e_j \in E(X).\)

Since cells of \(G\backslash X\) corespond to \(G\)-orbts, for every \(v \in V(X)\) there is some \(g \in G\) such that \(g\cdot v = v_i\) for some \(i\) and the analogous statement also holds for edges. Because the set of cells

is finite and \(X\) is path connected there must be some sufficiently large \(r_0\) so that \(C \subset B(p_0,r_0)\text{.}\)

Let's now prove Item 2. Suppose towards a contradiction that for some set \(s>0\) the subset \(R_s \subset G\) is infinite. Since \(B(p_0,s)\) is finite there must be some vertex \(v_0 \in B(p_0,s)\) such and an infinite subset \(\{g_1,g_2,\ldots\}\) such that

Let \(w_i = g_i^{-1}\cdot v_0\text{.}\) On the one hand \(w_i \in B(p_0,s)\text{,}\) on the other hand since \(B(p_0,s)\) is finite there must be infinitely many \(w_i\)'s that are equal, say

but then it follows that the elements

are all distinct, but all fix the the point \(v_0\text{.}\) This contradicts the hypothesis that the action of \(G\) on \(X\) is proper.

Finally we can prove Item 3. Consider first the set

And suppose towards a contradiction that \(\gen{S} \subsetneq G.\)

Claim: \(\gen S \cdot p_0 = V\text{.}\) Suppose this was not the case, let \(w_0 = g \cdot p_0\) be an element of minimal distance from \(\gen S \cdot p_0\text{.}\) Let \(u_0 \in \gen S \cdot p_0\) be a point closest to \(w_0\) and let \(\alpha\) be a path from \(u_0\) to \(w_0\) that realizes their distance.

On the one hand there is some \(s \in \gen S\) such that \(s \cdot p_0 = u_0\text{,}\) on the other hand there is some vertex \(u_1\) a distance 1 from \(u_0\) along the path \(\alpha\) which is strictly closer to \(w_0\) than \(u_0\text{.}\) The element \(s^{-1} \cdot u_1\) is distance \(1\) from \(p_0\text{.}\) There is some \(h \in G\) such that \(h \cdot p_0 = (s^{-1}\cdot u_1)\) and since \(s^{-1}\cdot u_1 \in h \cdot B(p_0,3\cdot r_0) \cap B(p_0,r_0) \neq \emptyset\) we have that \(h \in S\text{.}\) It now follows from equations above that

Thus, \(u_1 \in \gen S \cdot p_0\text{,}\) but this contradicts that \(u_0 \in \gen S \cdot p_0\) is as close as possible to \(w_0.\) This proves the claim.

So suppose finally towards a contradiction that \(\gen S \subsetneq G\text{.}\) Then there is some \(G \ni g \not\in \gen S\text{.}\) By the claim above there is some \(s\in \gen S\) such that \(s^{-1}\cdot (g\cdot p_0) = p_0\text{,}\) so that \(s^{-1}g\) fixes \(p_0\text{,}\) but then \(s^{-1}g \in S\) which implies that \(g \in \gen S\) which is a contradiction.

The proof above illustrates the potent combination of a proper, cocompact action by isometries. Such an action is typically called a geometric action. The lemma above gives an unexpected consequence:

Corollary 2.2.4.

If a group \(G\) acts geometrically on a path connected graph \(X\) then \(G\) is finitely generated.Recall that the quasi isometry class of a group \(G\) is the smallest quasi isometry class which contains all word metrics on \(G\text{.}\) In particular the statement below makes complete sense without having to specify some metric on \(G\text{.}\)

Theorem 2.2.5. The Svarc-Milnor Lemma.

If \(G\) acts geometrically on a geodesic metric space (e.g. a graph) \(X\text{,}\) then \(G\) is quasi-isometric to \(X\)sketch.

First note that by hypthesis \(G\cdot p_0\) is coarsely dense in \(X\) and in fact quasi isometric to \(X\text{.}\) So we need need only show that \(G\) is quasi isometric to \(G \cdot p_0 \subset X\text{.}\) We will show that the following map

is a quasi-isometric embedding. Since it is surjective the result will follow.

By Lemma 2.2.3, Item 3 \(S = R_{r_0}\) is a finite generating set of \(G\text{,}\) therefore(by Lemma 2.2.3, Item 3) so must be \(A = R_{3r_0}\text{.}\) We equip \(G\) with the finite generating set \(A\text{.}\) Note that for each \(a \in A\) we have

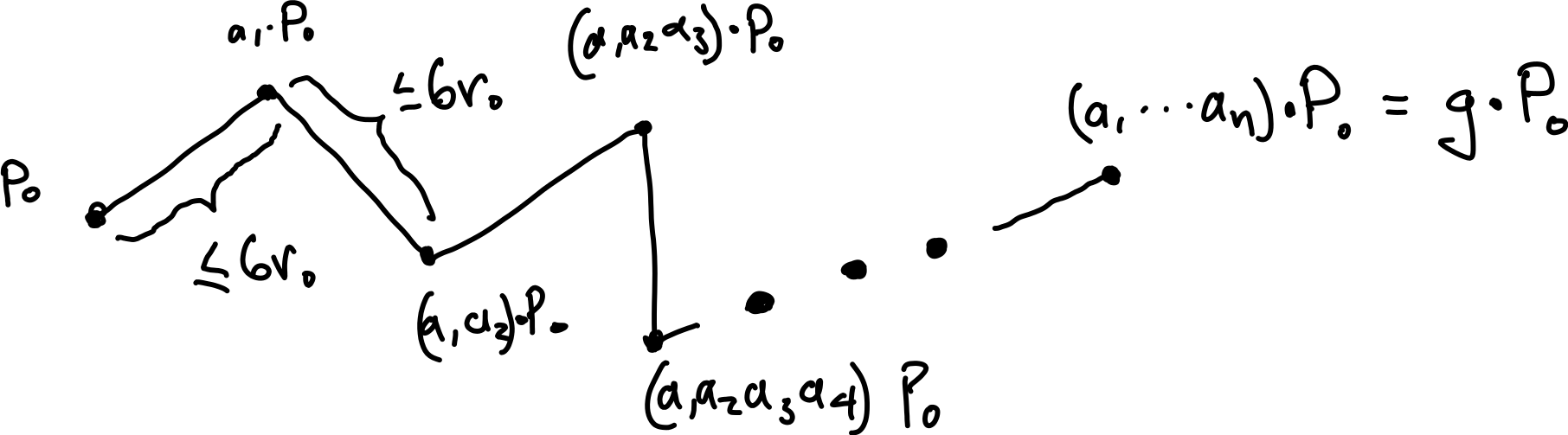

So if \(g = a_1\cdots a_n\) is a product of minimal length representing \(g \in G\text{,}\) i.e. \(d_A(1,g)=n\) then considering the broken path:

we have by the triangle inequality that

which is one inequality we need to show.

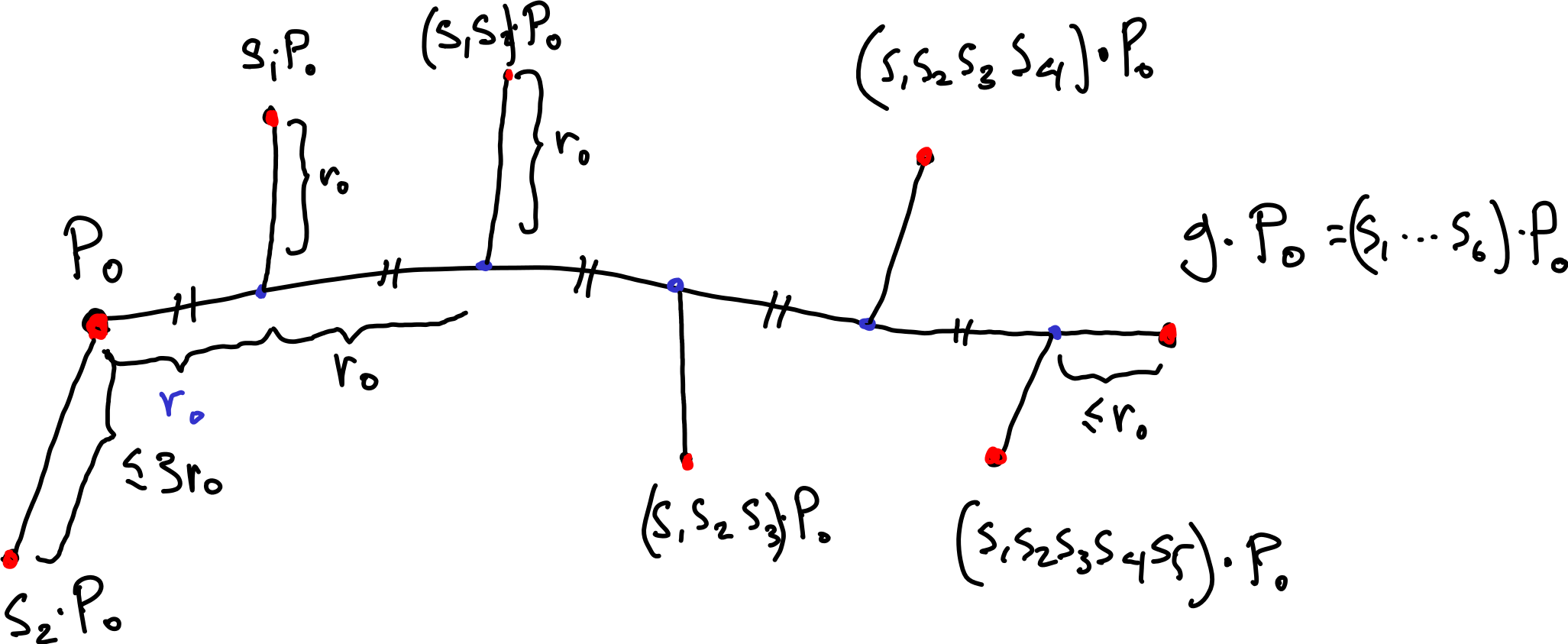

We now need to bound \(d_A(1,g)\) above by some linear function of \(d_X(p_0,g\cdot p_0)\text{.}\) This follows by noting that every point of \(X\) is a distance at most \(r_0\) from some point in \(G\cdot p_0\) ( Lemma 2.2.3, Item 1) and that every point in \(v\in G \cdot p_0 \cap B(p_1,3r_0)\) there is some \(a\) such that \(a \cdot p_0 = v\text{.}\) The picture below which is obtained by dividing the shortest path from \(P_0\) to \(g\cdot P_0\) into a minimal number of segments of length at most \(r_0\) implies that \(d_A(1,g) \leq \frac{1}{r_0}d_X(p_0,g\cdot p_0)+1\text{.}\)

At this point showing that \(f\) is a quasi isometry is straightforward.

From this we get the following, which gives us the ultimate limitiation of quasi-isometry Any finitely generated group \(G\) is quasi isometric to all its finite index subgroups.

Corollary 2.2.6.

The result above seems trivial for the following reason. If \((X,d)\) is a metric space and have a subset \(S \subset X\) and we equip \(S\) with the subspace metric \(d|_S\text{,}\) then \(S\) is isometrically embedded into \(X\) with respect to this metric. In particualr if \(S\) is coarsely dense in \(X\text{,}\) as is the case with a finite index subgroup, then \((S,d|_S)\) will be quasi isometric to \((X,d_X)\text{.}\) Let us call this the extrinsic metric on \(S\) from the embedding \(S\subset X\text{.}\) Above corollary is stronger than that. In particular any finite index subgroup of \(H\) is finitely generated so a finite generating set \(\gen A = H\) endows \(H\) with an intrinsic quasi isometry class.

The above corollary states that if \(H\leq G\) is a finite index subgroup of of a finitely generated group. Then \(H\) and \(G\) are quasi isometric with respect to their respective intrinsic quasi isometry classes.

Now it may happen that we have an injective homomorphism \(H \into G\) where both \(H\) and \(G\) are finitely generated but given aword metric \(d\) on \(G\) the induced extrinsic metric \(d|_H\) induced on \(H\) is not quasi isometric to any (intrinsic) word metric on \(H\text{.}\) In this case we say \(H\) is a distorted subgroup. We illustrate this with an example

Example 2.2.7. \(BS(1,2)\) the simplest weird group.

\(BS(1,2)\text{,}\) the Baumslag-Solitar group is a weird group. It has the following presentation:

Notice that the single relation gives the following commutation relation:

which means that every element can be expressed as a word of the form:

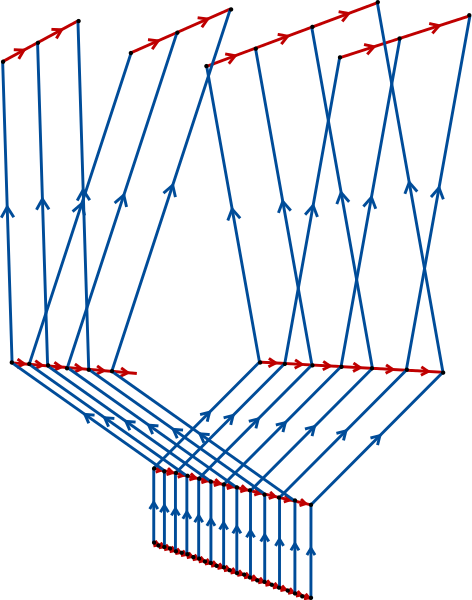

So far that doesn't seem weird, but its Caley graph looks like this:

Consider the homomorphism \(\phi:\ZZ \into BS(1,2)\) given by \(\psi(n) = a^n\text{.}\) In the next chapter we will see that \(\phi\) is injective. For now we can see this as \(\gen a \leq BS(1,2)\) as being a copy of \(\ZZ\) sitting in \(BS(1,2)\text{.}\)

We can now compare the standard metric \(d_\ZZ\) on \(\ZZ\) to the extrinsic metric \(d|_{\gen a}\) induced by its inclusion into \(BS(1,2)\text{.}\)

On the one hand we have \(d_\ZZ(1,a^n) = |n|\text{,}\) which is straightforward. Now the relation lets us rewrite, for example,

More generally we have \(a^{2^n} = t^nat^{-n}\text{,}\) so on the other hand we have two different metrics:

In other words this embedding \(\phi:\ZZ \into BS(1,2)\) exponentially distorts the intrinsic metric on \(\ZZ\text{.}\) In particular this embedding is not a quasi isometric embedding, as the latter only allows linear distortion.

We will say that groups \(G\) and \(H\) are abstractly commensurable if they have finite index subgroups \(K\leq G\) and \(K'\leq H\) which are isomorphic, i.e \(K \approx K'\text{.}\) Corollary 2.2.6 tells us that commensurable groups are quasi-isometric therefore we have the limitation that quasi isometry cannot distinguish between groups in a commensurability class.

Exercises 2.2.1 Exercises

1.

In the proof of Proposition 2.2.1 in equation (2.2.1), we didn't use the same formulation of quasi isometric embedding as in Definition 2.1.1. Explain why this is still okay.

Comment: If anything this is to emphasize that even the definition of a quasi isometric embedding is best left vague.

2.

A group acts on itself on the left and the right. Consider a generating set \(\gen A =G\text{,}\) and let \(d\) be the word metric on \(G\text{.}\)

- Show that the left action of \(G\) on itself is an action by isometries with respect to this metric.

- Show that the right action of \(G\) on itself is not generally by isometries with respect to this metric.

Hint: For part 2, \(G\) needs to be non abelian. Take a free group and just check out a few examples.

3.

Look at the proof of Proposition 2.2.1. Informally explain whether or not the argument could be generalized to distinguish \(\ZZ^n\) and \(\ZZ^m\) for general distinct \(m,n \in \ZZ_{\geq 0}\)

4.

Consider \(\cay{\{1\}}{\ZZ}\text{,}\) the standard Cayley graph for \(\ZZ\text{.}\) Consider the subgroup \(3\ZZ \leq \ZZ\text{.}\)- Sketch \(3\ZZ \leq \ZZ\) inside \(\cay{\{1\}}{\ZZ}\text{.}\)

- Draw the quotient \(3\ZZ\backslash\cay{\{1\}}{\ZZ}\)

5.

Let \(G\) be a finitely generated group and let \(K \leq G\) be a finite index subgroup. Let \(A\) be a finite generating set of \(G\text{.}\)

Prove that the induced action of \(K\) on \(\cay A G\) is co-compact.

Hint: The vertices of the quotient \(K\backslash \cay A G\) correspond to cosets.

6.

Prove Corollary 2.2.6.

Hint: Just combine all the previous results.

7.

Prove the commensurablity of finitely generated groups is an equivalence relation.

Hint: If \(K_1,K_2\leq G\) are finite index subgroups of \(G\text{,}\) then the intersection \(K_1\cap K_2\) is a finite index subgroup of \(K_1,K_2,\) and \(G\text{.}\)

8.

Let \(f:G \to H\) be a surjective group homorphism such that \(\ker(f)\) is finite. Prove that \(G\) is quasi isometric to \(H\)

Hint: \(G\) acts on the Cayley graph of \(H\) via the action \(g\cdot x = f(g)\cdot_H x\) where \(\cdot_H\) is the standard action of \(H\) on its Cayley graph.